Joni Mitchell Discusses Her New Book of Early Songs and Drawings

Joni Mitchell, in the foreword to “Morning Glory on the Vine,” her new book of lyrics and illustrations, explains that, in the early nineteen-seventies, just as her fervent and cavernous folk songs were finding a wide audience, she was growing less interested in making music than in drawing. “Once when I was sketching my audience in Central Park, they had to drag me onto the stage,” she writes. Though Mitchell is deeply beloved for her music—her album “Blue” is widely considered one of the greatest LPs of the album era and is still discussed, nearly fifty years later, in reverent, almost disbelieving whispers—she has consistently defined herself as a visual artist. “I have always thought of myself as a painter derailed by circumstance,” she told the Globe and Mail, in 2000. At the very least, painting was where she directed feelings of wonderment and relish. “I sing my sorrow and I paint my joy,” is how she put it.

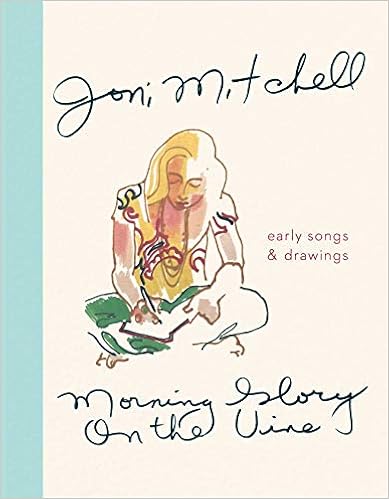

“Blue” was released in June of 1971. That fall, Mitchell gathered more than thirty drawings and watercolors in a ring binder and paired them with handwritten lyrics and bits of poetry. With the help of her manager and agent, she had the book hand-bound in Los Angeles, in an edition of a hundred. “They gave it to a Japanese fellow who used pale blue and silver foil on the cover and made it look, to me, like a bridal book,” Mitchell told me recently, in an e-mail. She called it “The Christmas Book” and gave it to her close friends as a holiday gift. This is the first time “The Christmas Book,” now titled “Morning Glory on the Vine,” has been widely available to the public. (It will be released on October 22nd.) “I always wanted to redo it and simplify the presentation, and we finally did,” she told me. Mitchell, who is seventy-five, has spoken about her struggles with Morgellons disease, and, in 2015, she had a brain aneurysm. But she remains cool, almost sanguine, about her legacy and its reverberations. “Work is meant to be seen,” she writes in the foreword. Why wouldn’t she share?

“Morning Glory on the Vine” is warm and tactile in a way that feels consonant with Mitchell’s songwriting. Many of her best tracks include precise, tantalizing details about home, both in the theoretical sense—home as a sort of broad, needling idea of comfort—and as a literal place, where a person stores her books and teacups and hiking boots. The latter felt vaguely radical in the nineteen-seventies; now it is increasingly sweet and rare to hear ordinary things like sweaters, coasters, brass bedposts, and white linens memorialized with such care and delicacy.

As the culture becomes more virtually oriented, music has, in some ways, started to feel less narratively tethered to place, which makes it striking to notice again how much of Mitchell’s work from this era is directly tied to Laurel Canyon, a wooded, mountainous section of the Hollywood Hills that, in the nineteen-sixties and seventies, nurtured a cabal of folksingers and artists.

(Graham Nash, Mitchell’s partner at the time, wrote “Our House,” which was recorded by Crosby, Stills & Nash in 1970, about the cozy, bohemian home that he shared with Mitchell there, on Lookout Mountain Avenue.) Mitchell made some drawings of their dining room: the view from the window, a basket of apples, flowers in a glass vase, her calico cat lounging on a pillow. They’re rich and abundant, saturated with deep, earthy color.

I asked Mitchell, who was born in Alberta, Canada, what it felt like to be in Laurel Canyon then—what brought her there, and why she stayed. “Well, prior to living in Laurel Canyon, I had been living in New York, in Chelsea, and it was noisy, and I was surrounded by gray concrete,” she said. “There was a concrete-block church there with a gold statue of a saint. Coming to California to look for a record deal with my then manager was like coming to the country, and Laurel Canyon was especially appealing to me because it was like where I came from. It was like the cottages at the lake, you know—it wasn’t adult housing. There was just something so warm and friendly and rustic about the Canyon,” she continued. “It was a beautiful place to me at the time, so I was happy to be there. It was a creative time. I was in a good relationship.”

It’s still important to Mitchell that the space she occupies reflects something about her aesthetic and her spirit. “I’m in a much bigger house now, which is good because I’ve turned it into an art gallery,” she told me. “I have lots of wall space to hang my paintings. I like to do my own decorating, and I like color around me, and both the little Laurel Canyon house and this house are very homey and comfortable.”

Read more here:

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultu ... d-drawings